The Terraform Namer Pattern: Making Consistent Naming Easy at Scale

Naming Is Infrastructure

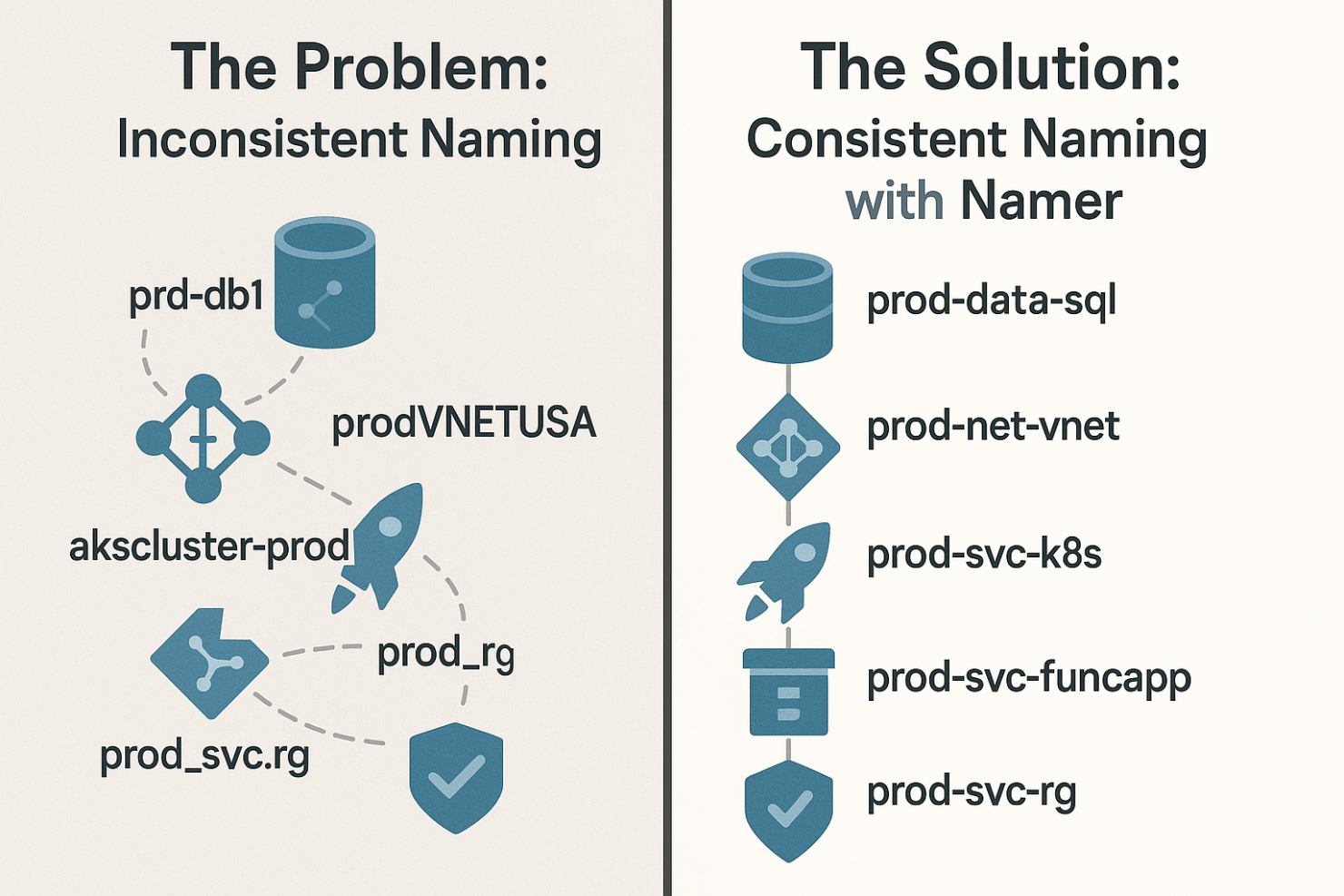

If you work in the cloud, you’ve probably run into this: a resource with a name that doesn’t quite follow the convention — or doesn’t follow any convention at all.

At first, it seems harmless.

However, as environments expand, teams scale and automation layers accumulate, inconsistent naming becomes a significant liability. CI/CD pipelines break. Logs become unreadable. Cross-environment lookups get fragile. And the next engineer wastes hours trying to guess what “rg-prod-east-xyz” is supposed to be.

In this post, I’ll share a pattern I’ve used to solve this at scale.

The Creeping Pain Point

I was working on a project with a customer that had a mature IT department with well-defined naming conventions — not just for VMs and switches, but for every on-prem resource you could imagine. To their credit, they’d already updated those standards to cover cloud resources, too, even though, at the time, they didn’t have anything in Azure yet.

I’ll admit I didn’t love the naming convention. It was a bit… ugly. But the customer’s always right. As we set up their new Azure environment using Terraform, we did our best to follow their guidelines.

But then the mistakes started.

Sometimes, someone forgets the correct order of the tokens in a resource name. Other times, a token would be left out. Or worse — someone would invent their own “extension” to the standard, tossing in an extra token to suit a team-specific use case.

Most of these mistakes were unintentional. But they caused real pain.

You might think, “No big deal — just fix the name and redeploy.”

Except we didn’t always catch the problem early. In some cases, the resource was already in service, with data or downstream dependencies. Changing the name meant replacing the resource. Which, in practice, meant we were stuck with an incorrectly named, non-compliant resource. Forever.

The Problem: The name Property Is Too Flexible

Every Azure resource has a name property, and that property accepts a plain string. Any string. No rules. No structure. It’s just a blob of characters — valid as long as Azure doesn’t reject it. But Azure’s naming rules are based on technical constraints, not your company’s naming conventions.

When building our Terraform modules, we followed the same pattern as the encapsulated resources. We created an input variable called name, typed it as a string, and left it up to the individual developer calling the module to follow the documented naming convention.

Outside the module, we tried to help with local variables like resource_prefix or env_tag to build partial names more consistently. But at the end of the day, we were still pasting together fragments of strings. It was entirely up to each developer to get it right.

And inevitably, someone didn’t.

Not because they didn’t care — but because strings are easy to get wrong. Forget a token, change the order, add an extra piece “just this once,” and suddenly, you’ve got a non-compliant name. Terraform doesn’t care. Azure doesn’t care. But your platform team does.

The result? We ended up with a mix of:

- Partially named resources that didn’t include environment or region

- Overloaded names that stuffed in too much information

- Resources that looked similar but didn’t follow the real pattern

Even with good intentions, we couldn’t enforce naming consistency — because the system provided no guardrails.

Naming That Just Works

Imagine every resource name is consistent. Compliant. Predictable. You don’t have to remember the order of tokens — or whether it’s “prod-east” or “east-prod.” You don’t even think about naming — because it’s generated for you, automatically, and always correct.

- Alerts and logs make sense, because the names they reference follow a known pattern.

- Terraform can locate resources by convention — using

datablocks and naming rules — instead of relying on remote outputs or hardcoded names. - You never have to choose between a painful resource migration or living with a non-compliant name.

And best of all? Developers can’t easily get it wrong.

They don’t pass in arbitrary strings anymore. Instead, they provide structured inputs — like environment, location, and service name — and let the naming logic handle the rest.

From Convention to Code

Before you can codify your naming convention, you need to have one.

As I mentioned earlier, many of my clients already had naming standards in place. But if you’re starting from scratch, Microsoft’s Cloud Adoption Framework is a great source of inspiration.

We adapted ideas from the CAF structure to match how the team actually thought about their infrastructure. For example:

rg-dev-centralus-svc-identity-0

Where:

| Token | Meaning |

|---|---|

rg |

Resource type (resource group) |

dev |

Environment (development) |

centralus |

Azure region |

svc |

Workload grouping (services) |

identity |

Application or service name |

0 |

Instance identifier (ordinal) |

We ordered tokens from general to specific to support predictable sorting, filtering, and scanning.

But the important part isn’t the order — it’s consistency.

Ask yourself: What matters most when scanning names? If it’s resource type, put it first. If it’s app name, lead with that. Pick an order that makes sense for your team and stick to it.

Once your structure is defined, the next step is to codify it.

We created a lightweight namer module with this interface:

variable "application" {

default = null

type = string

}

variable "environment" {

type = string

}

variable "instance" {

default = null

type = number

}

variable "location" {

type = string

}

variable "workload" {

type = string

}

The implementation is simple but purposeful:

output "resource_suffix" {

value = join("-", compact([

var.environment,

var.location,

var.workload,

var.application,

var.instance

]))

}

- Optional tokens (

application,instance) are placed last. - Required tokens are always present.

compact()strips outnullvalues, so unused fields don’t leave gaps.

Here’s how we typically use the namer module inside a resource module — like one that provisions a resource group:

module "namer" {

source = "../namer"

environment = var.environment

location = var.location

workload = var.workload

application = var.application

instance = var.instance

}

resource "azurerm_resource_group" "this" {

name = "rg-${module.namer.resource_suffix}"

location = var.location

}

And in the higher-level calling module:

module "identity_rg" {

source = "../modules/resource-group"

environment = "dev"

location = "centralus"

workload = "svc"

application = "identity"

instance = 0

}

The caller doesn’t have to build the name manually or remember the token order — they just pass structured values, and the module takes care of the rest.

💡 Notice in the resource module that the

nameronly supplies the resource suffix, not the full name. The resource module itself provides the prefix (rg). This separation of concerns keeps thenamermodule reusable — it can be embedded in any resource module.

Even Microsoft Built a Namer

We’re not the only ones to notice the need for codified naming.

Around the same time I wrote my first namer, Microsoft released an official Terraform module for naming Azure resources. Their module constructs names using inputs such as prefix, suffix. It’s flexible by design, which makes it broadly applicable across thousands of organizations.

And while we share the same goal (consistency), our approaches reflect different audiences:

Microsoft has to serve everyone. I just need to serve my clients — and get it right for them.

My namer module is opinionated by design. It expects structured inputs such as environment, location, workload, application, and instance. It handles optional tokens predictably, and the output is consistent.

This approach allows me to codify domain-specific structures. For example, one of my customers organizes infrastructure by program, grouped into solutions, each with multiple applications. That’s easy to reflect in a structured namer. For Microsoft, building a module that covers all such variations would be nearly impossible.

So while both modules solve the naming problem, they serve different needs.

Answering Common Objections

Developers Can Still Pass Garbage Into the Namer

Absolutely — and that’s a valid concern.

Just because we’ve wrapped naming in a module doesn’t mean the problem goes away. Developers can still pass invalid strings into location, environment, workload, or any of the other tokens. It’s entirely possible to write:

location = "CentralUs"

environment = "Development"

…and end up with a name that breaks consistency or violates Azure constraints.

The problem isn’t the module — it’s unvalidated input.

Terraform gives us tools to fix this, using validation blocks on input variables:

variable "location" {

type = string

validation {

condition = contains(["centralus", "eastus2", "westeurope"], var.location)

error_message = "Location must be one of: centralus, eastus2, westeurope."

}

}

variable "environment" {

type = string

validation {

condition = contains(["dev", "test", "prod"], var.environment)

error_message = "Environment must be one of: dev, test, prod."

}

}

These constraints eliminate “almost right” values like Production, east-us, or qa1 — small inconsistencies that erode standardization over time.

And this is another reason the module matters: it centralizes validation logic.

Even if a downstream resource module forgets to validate environment or location, the namer module ensures only known-good values are accepted. That makes it easier to scale across teams and repositories without trusting everyone to remember every rule, every time.

HashiCorp Says to Avoid Nested Modules

HashiCorp’s guidance recommends being cautious with module composition. Specifically, they warn that deeply nested modules can make Terraform harder to reuse, test, and understand. And they’re right — in general.

But let’s unpack what that guidance actually means.

⚠️ The problem isn’t nesting itself — it’s unstructured, deep, or unnecessary nesting.

In our case, we’re embedding a small, single-purpose utility module — the namer — inside a resource-specific module (like one that provisions a resource group or app service). That’s not deep or complex. It’s deliberate encapsulation.

Here’s why this pattern works well in practice:

- No added control flow — The

namerhas no dependencies, branching, or side effects. It just returns a string. - Improved DRY and correctness — Without it, every resource module would need to duplicate the naming logic — and probably do it inconsistently.

- Testable in isolation — The

namercan be unit-tested separately or used directly outside nested contexts. - Simpler for consumers — Callers only provide structured context. They don’t need to understand or maintain the naming format.

At scale, where consistency is crucial and modules are reused across teams and environments, this lightweight composition pattern has paid off again and again.

A Lot of Work Just to Build a String

At first glance, the namer module might look like overkill. It just produces a formatted string, right?

But in practice, we’ve extended the namer to cover a variety of real-world scenarios — especially the inconsistent naming requirements across Azure services.

Different Azure resources have different naming rules:

- Some require lowercase alphanumeric only

- Some disallow hyphens

- Some have character limits as low as 24

- Some allow longer, more expressive names

Besides the full resource suffix, here’s what the module provides:

output "resource_suffix" {

description = "A standardized resource suffix combining environment, location, workload, application, and instance identifiers. Use this with a resource type prefix to create consistent resource names across your infrastructure."

value = local.resource_suffix

}

output "resource_suffix_compact" {

description = "A compact version of the resource suffix with all hyphens removed. Useful for resources with strict length limitations or naming conventions that don't allow hyphens."

value = replace(local.resource_suffix, "-", "")

}

output "resource_suffix_short" {

description = "A shortened resource suffix using abbreviated environment and location codes. Designed for resources with restrictive naming length requirements while maintaining readability."

value = local.resource_suffix_short

}

output "resource_suffix_short_compact" {

description = "A shortened and compact resource suffix with abbreviated codes and no hyphens. Ideal for resources with stringent length limitations."

value = replace(local.resource_suffix_short, "-", "")

}

By centralizing the logic, we:

- Reduce duplication — One implementation, many consumers

- Enforce consistency — Developers can’t “almost follow” the pattern

- Support constraints — Compact and short formats are pre-baked

And as a bonus?

We also generate standardized tags:

output "tags" {

description = "Standardized tags including application, creation date, DevOps team, environment, owner, repository, source, and workspace information. These tags follow organizational tagging standards for resource management and cost allocation."

value = local.tags

}

With just a few more input variables, the same namer module can output tagging dictionaries that:

- Drive cost management and showback

- Enforce platform tagging policy

- Improve search and grouping in the Azure Portal

- Make incident response and ownership tracking easier

💡 The

namerisn’t about abstraction for abstraction’s sake. It’s about operational predictability and platform integrity.

Make the Right Thing the Easy Thing

Naming might seem like a minor detail — until it’s not. When naming breaks down, platforms become harder to navigate, automation becomes brittle, and developers waste time chasing avoidable errors.

The Terraform namer pattern isn’t magic. It’s a small, opinionated module that codifies your naming strategy, gives teams a consistent interface, and reduces the surface area for human error.

By investing a little upfront effort to centralize and automate naming (and tagging), you gain:

- Predictable infrastructure that’s easier to support

- A shared language for your team and your tools

- Guardrails that catch problems before they land in production

- A stronger foundation for growth and reuse

If you’re tired of fixing naming issues after the fact — or if you’re scaling a Terraform-based platform across teams — this pattern can save you headaches later.

Need Help Putting This Pattern to Work?

I’ve seen this pattern save teams from endless frustration — and I’ve helped organizations of all sizes implement it across their platforms.

If you’re wrestling with naming drift, Terraform sprawl, or platform inconsistencies, let’s talk.

👉 Connect with me on LinkedIn — I’d love to hear what you’re building and see how I can help.